I have been looking into the 19th century photography, as a central means to invent and define the ‘other’. It is a very interesting part of imperial and of photographic history, and it has become the core of my research. This month I publish on this in the leading literary magazine DW B.

Check the article, in Dutch:

DW B – Antropometrie

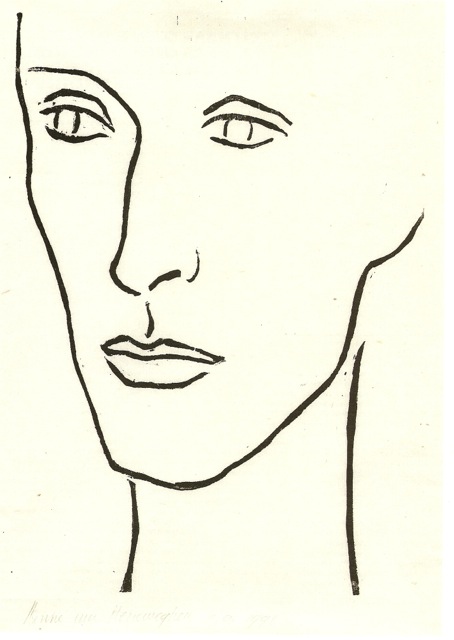

Before photography became an important means of image production, anthropologists were trying to define and distinguish ‘races’ with measurement and drawings. Photography was very much welcomed in the anthropological field; it was thought to be more ‘precise’ and therefore ‘scientific’. The then leading French anthropologist Paul Broca wrote in his Instructions générales sur l’anthropologie (1865)1:

“On reproduira par la photographie :

1°) les têtes nues qui devront toujours, sans exception, être prises exactement de face, ou exactement de profil, les autres points de vue ne pouvant être d’aucune utilité ;

2°) des portraits en pied, pris exactement de face, le sujet debout, nu autant que possible, et les bras pendant de chaque côté du corps. Toutefois, les portraits en pied avec l’accoutrement caractéristique de la tribu ont aussi leur importance”.

Free translation: “Shall be reproduced by photography:

1) naked heads, always taken exactly frontal and exactly in profile, the other viewpoints being of no interest at all;

2) Full length portraits, taken exactly frontal, the subject standing, as naked as possible, and the arms pending on each side of the body. All the while, full length portraits with tribal attire are also of interest.”

I found this fragment in the article by Pierre-Jérôme Jehel (see link at side) and I haven’t studied the complete text by Broca yet. But I am astonished that an exactitude – with the aim of measuring – would be expected from this method if you do not discuss or ‘instruct’ the distance between camera and model, the height of the lens, and even the type of lens used as well as the light.

Many photographers used the ‘Broca method’ between 1860 and 1880, with the aim of creating general images, ‘typologies’ of people. But the photography resulted in the opposite: each photograph taken emphasized the specific, the uniqueness of the photographed individual. The more photographs were created, the more the realities multiplied instead of leading to a single conclusion. So by 1880, the scientific ambition of the method was left by most photographers.

In the meantime, and much less scientific, thousands of photographs were made, printed and spread on postcards. These images emphasized the ‘Otherness’: lip-discs, haircuts, jewelry, scarification, and many times, the nakedness of the others – with a preference to young girls in poses with, from a Western point of view, a sexual connotation.

I write about this and about my project in the 160th anniversary edition of the dutch-language magazine DW B. You can find the magazine in literary bookshops in Belgium and the Netherlands, or order it, via the link to the side.

I thank DW B for the attention to my work, especially the writer Koen Peeters. I also thank Ingeborg Eggink of the National Museum of World Cultures (NL) for the kind permission to use the sensitive images.

1In: Pierre-Jérôme Jehel, Une illusion photographique, Journal des anthropologues [En ligne], 80-81 | 2000, mis en ligne le 28 octobre 2010. URL : http://jda.revues.org/3139